“What an ornament to a river to see that glowing gem floating in contact with its waters!” – Henry David Thoreau, writing about the drake Wood Duck

Yesterday was World Photography Day and on social media I wrote briefly about my beginnings, five years ago when I set out to photograph wood ducks at my favorite, local wetland. I thought I would re-publish this blog to expand on my post. Five years later, in 2019, I have the incredible luxury of walking a relatively short, well-groomed trail and viewing these beautiful ducks from a wooden blind at that same pond. Back in 2014 and 2015, it wasn’t quite so simple. Still, after all these years, easy or difficult, I feel that same thrill when a wood duck of any age or molt enters the scene. There’s just something special about those scrappy dabblers. Here is the tale of how it all began. If you have already read this and aren’t interested in the refresher, please jump to the bottom for a full suite of wood duck images, including some newly released photos from the spring and summer of 2019.

Autumn 2014

The drake Wood Duck in full nuptial plumage is one of the most beautiful and celebrated ducks in the world. However, photographing Wood Ducks, especially in upstate New York, is extremely challenging. There are parts of the country where they are found in more public areas. These ducks are tame and can be approached and photographed with a fair amount of ease. In New York they are very wild and wary of humans.

In the autumn of 2014 I set out to try to photograph these elusive, wild ducks at a local wetland preserve. I invested in a telephoto lens. Throughout September and early October I explored the pond, trudging deeper and deeper into the woods and away from trails until I found a spot where the Wood Ducks would gather. By late September I had moderate success in observing them by concealing myself and my camera using a camouflage cloth.

Winters in New York can be cold and the lakes and ponds freeze over. Wood Ducks migrate south looking for a suitable climate. During those months while the ducks were away I began preparing for their return. I made several trips to the local outdoors store and purchased a variety of camouflage items, all compact and portable because I would have to carry them in and back out again for every visit. I also studied Wood Duck behaviors. I scoured the internet and read all the books I could find about them. I made a mental list of the behaviors I hoped to observe. And I anxiously awaited their return.

During those months away, Wood Ducks pair up to choose mates for breeding season. When they migrate to their summer home the drake follows the hen to her native nesting site. It is also common to find a second, interloper drake waiting in the wings, hoping to step in if the first drake doesn’t work out.

Spring 2015

In April 2015 the lakes and ponds started to thaw and I heard reports of local Wood Duck sightings. At my first opportunity I packed up my newly purchased gear and embarked on a reconnaissance mission to seek them out at my local wetland. When I arrived at the main, open section of the pond I saw only Geese. The ice had thawed and the pond was wide open, so I trudged through the trails and beyond. Far off the main trail and through gaps in the trees I spotted three Wood Ducks, one mated pair and one interloper drake. They had been perching on a log and enjoying the warmth of the sun.

That day I didn’t set up a blind. I only snapped a few photos and then scoped the area to determine where I would set up for my next, longer visit.

Courtship on the Pond

During breeding season the drake Wood Duck of a mated pair will often groom his mate as a show of affection and to enhance the pair bond. This was one key behavior I wanted to observe and photograph. For the next several weeks I trekked back out to the pond and set up a blind at the edge of the shore. After multiple visits I had only seen minimal interaction between two pairs. That spot seemed promising so I continued to set up my blind and keep watch.

One afternoon, I peeked out to see two canoers working their way through the pond. At that point ducks I hadn’t even seen flew out from the reeds. The canoers didn’t stay long but I knew it would be hours before any ducks would return. However, courtship season would end soon and I knew my time was short, so I waited. After two hours a pair of Mallards made an appearance. They were followed shortly by a two separate Wood Ducks pairs. Both of these pairs swam through the area and then each stopped for a short time to groom each other within my view. I had witnessed and photographed the first behavior on my list. My mission would be a success.

Boy’s Club

When the hens are on the nest and incubating eggs, the drakes gather together in small loosely knit social groups. In early May I was able to witness this gathering of drakes that I had previously only read about right outside my blind. On that slightly overcast afternoon three drakes climbed onto a log and spent several minutes resting and preening. In the image below the middle drake is chastising the front duck for invading its space. The front drake moved a few inches to his right and then they were all content.

First Brood

During late spring a silence fell over the pond. The drakes and hens no longer spent time together. Most duck species only stay mated during breeding and early nesting. Ducklings are fairly independent at birth and only require protection and brooding by the hen. Having the male present could also draw unwanted attention to the young fledglings and alert predators. Once the hens are deep into nesting, the pair bond is severed.

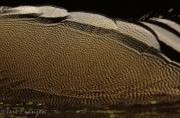

At this point in the cycle the drakes start molting into summer plumage and become more retiring. They would soon lose their flight feathers and don’t want to be easy prey, or “sitting ducks”. The hens are very scarce because they are nesting. The pond feels almost desolate.

During that time I continued to set up my blind. On a Sunday afternoon in late May I was again rewarded for my patience. I had set up in a completely new and more open section of the pond and waited. For several hours I watched two molting drakes preen far across the water and beyond the reach of my lens. Just after 3:30pm I looked over to my left to see a hen Wood Duck swimming in my direction. Then she turned. Behind her seven babies followed her lead, one of them riding shotgun on her tail feathers. The troupe swam across the pond in front of me and then out of view. This twenty second encounter would be the first of many extremely rewarding afternoons watching ducklings.

Inter-species Nest Parasitism

Two weeks after my first duckling sighting I had to move into the pond, literally, sitting with my feet in water and seated just barely out of the water. The reeds had grown so much that I had lost visibility at my early springtime spot. During those later outings I wore knee-high boots and used sticks and a small, inflatable pillow for a seat. Previously my blind had been a façade, only shielding me from the front. At this point I also added a second cloth to hide my back because ducks would sometimes swim behind me.

One early June morning a hen Wood Duck climbed onto a log, followed by three very young Wood Ducks and one young Hooded Merganser. Wood Ducks and Hooded Mergansers share nesting habitat and the hen of one species will often one lay one or more eggs in another hen’s nest, a behavior known as inter-species nest parasitism. The nesting hen will raise the foster duckling as her own. As I watched this small family the four ducklings stayed close together and the hen brooded the Merganser baby along with her own.

Duckling Curiosity

Later that month, as I settled into my blind, I looked over to notice a Red Raspberry slime mold that had appeared since the last time I was at the pond. Mid-afternoon a family of three Wood ducklings climbed up onto that same log. The young ducks attempted to brood, briefly, under the hen. But, as with all toddlers, they didn’t sit still for very long. As they walked across the log, they noticed the slime mold. In the image below, the baby on the right had just taken a small bite. Young Wood Ducklings are drawn to movement or bright objects and will often test these curiosities to see if they are edible. In this case, the vivid colors of that slime mold had caught their attention. Following this encounter I researched the edibility of this fungus and could not find anything documenting its toxicity. It does not appear to have been poisonous.

Convergence of the Families

Throughout the spring and early summer I had only seen individual Wood Duck families and typically for a brief time. In mid-July I set my blind near more open water. That morning five Wood Duck families ranging in ages from one week to seven weeks old came into the area. Most of them stayed for several hours and the activity was constant. One of those families included a Hooded Merganser duckling. Statistics have shown that the survival of a foster duckling is about the same as its siblings. I believe that to be the group I had seen earlier in the season.

Wood Ducks are dabblers and typically forage at or just below the water’s surface for vegetation. They rarely dive and only if there is something very interesting further below the surface. However, on that day one of the family groups dove frequently. One duck would dive and disappear and the others would follow, including the Mother. This was the same family that I had seen that day with the Hooded Merganser so I speculate that they might have been influenced by the diving behavior of a foster sibling. Since diving is not unheard of for Wood Ducks it would be impossible to know for certain.

Between five and seven weeks old young Wood Ducks will start to become independent. The ducklings will begin to stray and separate from their mothers. However, on that same July day I saw one large brood of six ducklings that was about seven weeks old. They all stayed very close to the mother hen. And at one point all of them crowded together on the same log for several minutes. This gave me a chance to observe the development characteristics of sub-adult ducks. At seven weeks these ducks were not quite fully developed and their wings had a little more growing to do. The males had a prominent, white saddle marking on their faces which distinguished them from the females.

On that same afternoon I also saw a fully eclipsed drake. During the summer the adult male Wood Duck loses his nuptial plumage and molts into what is called eclipse plumage. In this plumage the male looks very similar to a hen or a sub-adult male. One distinct difference from the female is the saddle marking on the male’s face. The red eye also distinguishes this male from the young drake as well as the hen.

Wood Duck Diet

In late summer most Wood Duck families have dispersed and separated from their parents. They will often spend time with siblings. It is also common to see them on their own. In mid-September this young drake Wood Duck swam solo into my view from my blind. He suddenly grabbed at something from beneath a lily pad. I turned my lens toward him and realized he had captured a frog by the hind leg. As I watched he worked to maneuver the frog around, flipping it upside down and turning it 180 degrees. He proceeded to swallow the frog whole, head first. The young Wood Duck’s diet is typically a mix of vegetation, insects and small invertebrates and is primarily influenced by habitat and opportunity. As I witnessed, they are not above snacking on something more substantial.

Autumn 2015 – Last Drake of the Season

During autumn Wood Ducks leave the pond in search of their winter homes. Ducks from the north pass through and take their place for a short time before traveling further south. The transient ducks can be extremely skittish. I noticed right away, even though I was well concealed, that any movement of my lens or noise would attract their attention. Then they would leave. It was more important to let the ducks rest than for me to capture photos. Migration is tough on a bird and I didn’t want to stress them any further. My last view of Wood Ducks that autumn was a small flock flying over the pond. I waved good-bye and bid adieu to my dear friends.

Throughout the spring and summer of 2015 I spent countless hours crouched in a blind, some days wet, cold and shivering while others stifled and sweating. I had been bitten by bugs and ticks, found spiders and caterpillars in my hair and all over my clothes. During that time I witnessed Wood Ducks as they courted. I watched families just starting out and experienced their growth and development until they entered adulthood. They hadn’t even known I was present and yet I knew them as comrades. I had successfully photographed wild Wood Ducks in upstate New York.

All images and text copyright Teri Franzen 2015-2017. Photographing Wood Ducks in the Wild was published as a feature length article in “Wildlife Photographic Magazine” in 2016.

More writings from Brick Pond

- Fourteen Days in a Blind (includes video)

- Blind Luck (includes video)

- Napkin Dreams and Wetland Wonders (includes video)

- Sights and Sounds of Brick Pond (video from my early exploits)

- Chomper Goes Home (video of a snapping turtle release at Brick Pond)

- Woody on Ice

Wood Duck Gallery